If you’ve read this far you’ve got the goods to design a monster, so now it’s time to think of your creation as part of the bigger picture, as a denizen of a universe. You’ll need to consider how your monster relates to the world around it as well as other monsters so that you can determine how to role-play them and how they will act in combat.

There are loose themes that the most monsters will fit in if your campaign fits into any of the better-known genres. The themes for monsters are based on creature type, location and its association with other creatures.

Natural Beast

The behavior of these creatures is determined by their place within an eco system. The fish eat the flies, the bear it’s the fish, the birds live in the trees and the worms don’t like the sun. Often the wild beasts in D&D games are modeled after real ecosystems, and so when your design your wooly mammoth you likely have an artic area in mind. Things to consider are climate, weather, size of the ecosystem, biological diversity and environmental interference.

Wild beasts act on what humans like to call instinctual behavior, pattered actions that are informed by evolution and adaptation so that the species is effective. This behavior often falls into either the predator or prey column, though each creature will hunt and be hunted in kind in a full ecosystem. Various predatory strategies exist, but amongst them are pack tactics (such as wolves or dolphins), lone stalkers and hit and run (like sharks, adders and hawks), scavengers (as in vultures), ambushers or trappers (like moray eels and spiders), hulks (like whales) and swarming creatures (like army ants).

In many cases the PCs will be the prey for whatever they are fighting, and the relevant tactics of that animal should be considered. Predators are most interested in feeding to insure their continued survival so for most there will come a point when it’s time to turn tail and run. Spiders that spin webs don’t typically stick around after their prey has broken free from their web, nor will lions continue to attack after the alpha female has been slain. In nature not every fight is to the death.

In most other cases the natural beast will fight the party because they are either on the defensive or they have been trained to do so. Some dogs are loyal to the end, but for most there comes a breaking point where they will suffer no more abuse in service of their master. Some creatures will die in an attempt to protect their young, though some creatures are more cowardly or simply don’t exhibit parental behaviors.

Elemental

In most human cultures myths exist that describe elemental beings that are born of the ingredients of the cosmos. They are material made living. Since these creatures don’t actually exist, the ball will be in your court once you decide on your vision and how they will act. Some of the more common tropes for elementals include anthropomorphizing, guardianship or chaotic behavior. They take on the personality of their element (fire elementals could be aggressive and rash), they defend some sacred natural place, or they wreck up the place, converting it back into the primordial nature.

Devine beings, good or evil

If elementals are the components of the universe made active, devine beings are the representation or moral position, a faith or a set of beliefs. These creatures include angles, demons, devils, cherubs, seraphim and so on. These creatures typically embody a Judeo/Christian/Islamic perspective though other faiths have just as inventive critters, such as Tiamat, the Babylonian goddess of the oceans, or Quetzalcoatl, the feathered serpent god of Mesoamerica.

You can base the behavior of your divine creatures off of the florid and lengthy descriptions made available in many religious texts, or you can develop your own themes. These beings can serve to their creator and its values to their last or they can be subjected to temptation like the biblical story of the fall of the arch angle Lucifer.

Constructs

I like to call these D&D robots. They are typically machines or animated soulless matter. This creatures usually sport low intelligences and simply follow the routines or commands given to them by their creator, in this way they are purpose driven, a quality that few other creatures sport. They are a favorite choice for encounters that have a puzzle element if you include a shut down sequence or command word, the party can defeat the D&D robots or they can try to outwit their simple mechanical minds. Constructs can take the appearance of anything that could be fabricated, though they are often seen posing as statues until the party steps on the pressure plate. The Warforged of Ebberon are a recognizable form of construct.

Tribal

A lot of fiction finds its genesis in the fascinations of forgotten eras and then those themes persist. From the colonial era we have many myths about primitives, savage and primal races in Africa, the Americas and Oceana. Though the misconceptions about these cultures were definitely racist, you can still make use of this old style of speculative fiction to inform your monster design. Although those old Europeans may have been lying through their teeth, you can make shamanistic spirits that can and will kill the party. Tribal cultures are often marked by exotic social structures and beliefs akin to superstitions. I say “akin to superstitions” because if the goddess of the earth actual shows up and demands sacrifices you’re not superstitious, you’re pragmatic. Much of the tribal theme is tied into the appearances, a lot of body paint and not a lot of clothing, or if in cold climates many furs and animal skins; a very “from the land” aesthetic.

Civilized

The process of our human civilization to date has lead us to increasing urbanization and so many D&D campaign settings adopt this model, though you can make the goal of a civilization anything you want because you’re the DM. Civilizations on a base level are the sum of their constituents, their ideas and their activities. Your civilization can be anywhere along the track of its development, it could be in the stone age or nearing its goal. Your monsters might exist anywhere within the social organization of the civilization. They may be the heads of large associations or they might be marginalized creatures thriving off of the scraps jettisoned into civilizations wake. There are any number of reasons why your monsters might be in that position, too many to discuss here, the key is to realize your monster’s place in the world.

Horror from beyond time and space

H.P. Lovecraft’s work has left a distinct impression on the world, so tentacled elder gods usually find their way into every D&D game at some point (most commonly referred to in 4e D&D as Aberrations. Beyond being soul destroying what’s important about these creatures is that they hail from some place so strange that thinking about it drives mortals to insanity and that beings from that place hate you very much. These creatures may employ a wide range of tactics to further their goals, from infiltrating the institutions of mortals or by body swapping. Sometimes these creatures are more direct and simply open a hole in the universe and allow the murder to flow from one world to the next.

Undead

There is likely no other topic upon which so much fiction is built than the undead. These very popular creatures have been explored so thoroughly that examples of them participating in all of the above themes are in place in the cannon of some fiction or another. The undead can be deeply rooted in the folk lore from which the rise or they can be the super modern teen angst sort. In folk lore the undead are subjected to particular rules, with very specific conditions that need to be met for them to be destroyed, as well as what they are capable of. These older ideas about undead can go a long way to aiding a very old-school feel to your game, with ghasts that drain levels and cause all sorts of trouble that 4e players tremble and protest at the thought of.

The list goes on. So how do you tie your monsters together as a cohesive whole. There are a few straight forward techniques that you can make use of that require little time on your behalf. They include the use of templates, common powers and relationship flow charts.

Templates

These are a pretty straight forward way of changing any existing creature into a creature of a new sort. Say you came up with an awesome idea of fire breathing marine life and wanted to reuse the idea to create other fishy beings, you could produce a template for yourself to increase the ease of editing existing monsters from the manuals or other sources. Templates are first explained on page 174 of the DMG, and though the templates presented mostly effect the given defenses of the creatures you can apply this idea to a greater number of monster features. Templates can also address ideology or the perspective of the character, or even impose a moral code.

You can also create templates that are designed to alter the mechanical assumptions of monsters and combat in general. One such template that I use often is designed to speed up combat for when I want the PCs to feel like they are in a threatening environment but don’t want to spend too much of the night on having the party attacked by highwaymen for the thousandth time, something not worth an hour of my life. This template cuts the HP of the monster while doubling their damage output. The template also drops all the monsters defenses by two while raising their attack score by the same amount. The result is that the fight is typically just as demanding of the party’s healing surges and other resources, but because heavier blows are traded more often the combat is resolved without such a great investment of time.

There are an endless number of ways you can reskin D&D combat using templates if you’re inventive enough. Experiment with using templates that accentuate particular mechanical elements in order to shift the focus of combat, such as having all creatures gain an increased benefit from cover or combat advantage. Once the party learns that the monsters get +4 to attack when flanking they are bound to change their tactics.

Common Powers

They’re almost like a secret handshake that your party isn’t cool enough to know. One sure fire way to connect different monsters in the eyes of the players is by giving them all one power in common. This works exceptionally well for creatures that are supposed to be part of an organization and can be used to dramatic effect within games that rely on suspense or the uncovering of evidence as this common power becomes an important clue.

Another benefit of monsters sharing a power is that all of the monsters become easier to run in combat as there are fewer quirks for you to concern yourself with. You can also reduce clutter by only producing the power once, saving valuable table space, ink, trees and time.

Relationship Trees

These can look like the hierarchy of a government or they can look like food webs, depending upon the creatures in question. By including notes next to creature entries you can create quick reference documents to remind you of the relationships of your monsters. Even if you have no intent on using the flow chart as an aid at the table, the act of creating it can help you make considerations about your monsters that you would not have done otherwise.

Don’t Limit Yourself

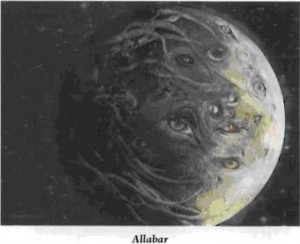

If you think an idea would be cool for a monster, go for it no matter how crazy the idea seems. If you peel through the monster manuals you’ll find no end of late heroic tier humanoids that are nearly identical; if you try something new you might add something to the game and improve it. For what it’s worth I think you should try to beat this:

If your party has to fight a whole planet then there’s not much else there left to fight, or is there? Roll initiative, you’re being fired upon by April 20, 1957! Challenge the key presumptions of the game and you only stand to learn from your experience.

So that just about wraps this discussion of creating monsters up for now. There’s a lot more on the topic to be considered of course, but that’s another story for another time. If you’ve worked through all these articles, fashioning your creation as you likely disagree with me on a few points but that just means that you’ve developed a style of your own. Good luck with you new monsters, I hope for their sake that they make it through at least their first encounter.

Related reading:

- Building Better Monsters Part 1: Meet Your Maker, Monster

- Building Better Monsters Part 2: More Than the Sum of Its Parts

- Building Better Monsters Part 3: Making the Monster Fit the Bill

Looking for instant updates? Subscribe to the Dungeon’s Master feed!

Looking for instant updates? Subscribe to the Dungeon’s Master feed!

2 replies on “Building Better Monsters Part 4: Monster Themes and Implementing Your Designs”

[…] Building Better Monsters Part 4: Monster Themes and Implementing Your Designs […]

Nice write up. Just a few things:

It seems that in your hatred of XP (from Part 3) and it’s various usage in rewards and encounter design, you didn’t mention anything about the link between the budgeting part of XP per an encounter (Part 3) and the roles of monsters (Part 2) and themes/implementing your designs (Part 4) which I think is vital for actually creating encounters. “More than the sum of it’s parts,” right?

An example of an encounter could be a pack of Dire Wolves will attack with a wolf pack type mentality and the monsters would be skirmisher type mobs. Another would be an Air Ship Captain (leader) with numerous deckhands (soldiers) and archers (artillery) — a military type encounter. The third type may be a Vampire (solo leader) with a bunch of succubus (minions), the all elusive Villain.

I like how you explained in detail about individual monster creation and themes, but I’d like to hear more about bringing the parts together and how encounter design plays a role in selecting/creating monsters.